When adults put their own social affirmation ahead of truth and the defense of children — what aren’t they willing to accept?

As an anorexic teenage gymnast, my disordered and self-destructive behaviors were endorsed and furthered by all of the adults in my life, viewed as a necessary sacrifice to win.

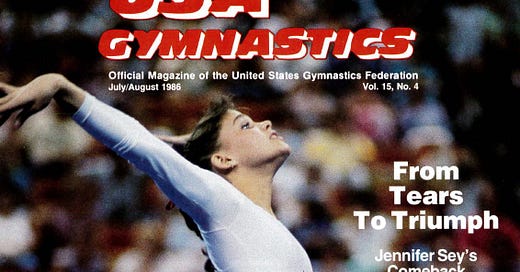

I was anorexic as a teenager. It was brought on by my training as an elite gymnast, though who knows if it would have happened anyway. I certainly fit the profile — a perfectionist, type-A personality. And while anorexia was “trending” in the 1980s, the extremely weight-obsessed culture in the sport of gymnastics exacerbated what was happening in the culture at large. This is me at the American Cup when I was 18-years-old.

Even now, in a throwback to my disordered thinking, I look at this picture and think: I look fine. I could have been thinner. Maybe there was nothing wrong after all.

I know that is ridiculous. I was close to 20, I had no boobs, I didn’t menstruate and I subsisted on a few hundred calories a day. I basically ate apples and yogurt. And whether I appeared to be on the brink of starvation or not, my obsession with weight and calorie intake was unquestionably disordered, to the point of being deranged.

Whether or not I would have become anorexic even if I never set foot in a gym is unknowable. But it is undeniable that the coaching environment I grew up in accelerated any tendencies I might have had.

My coaches were hyper-focused on weight. We were weighed in at the beginning and end of practice. Our weight was recorded in a chart and frequently announced on the loud speaker as a means of humiliation. If we gained a quarter of a pound, we were berated as fat and disgusting and forced to do “extra conditioning” which was basically running laps in a Saran Wrap like sweat suit.

One young, junior national team gymnast was humiliated by our head coach when the child weighed in at 70-something pounds at 10 or 11 years old: “Do you want to look like your parents?!”

This athlete’s parents were overweight. Her mother was present in the gym when this cruel nonsense was spewed. No one argued. Not the athletes, not the parents watching along with the mom from the balcony, not another coach in the gym. It was par for the course, and considered acceptably within the boundaries of tough coaching.

As young athletes we were told: lose 2 pounds by tomorrow, by any means necessary (yes, they were that explicit). We were screamed at: “I don’t coach fat gymnasts!” And “You’re not going to nationals if you don’t lose 3 pounds. You’re an embarrassment!” I was told by a prominent judge: “Doing gymnastics at your weight is like doing the sport with a ten pound bag of sugar strapped to your back.” The judge also said: “Don’t wear bangs, they make your face look fat.”

We were tiny (not that it would be ok to bully us this way if we weren’t). I weighed under 100 pounds. I didn’t get my period until I was 19 years old because my body fat was so low. At national team training camps we had our body fast tested regularly. We were all under 5%, often in the 2-3% range.

The bullying and fat-shaming went on and on. But we took it, hoping to please our coaches and earn a coveted spot, not just on the national team but on the podium at national competitions. Wins like this came with honor, not just for the child competing, but for the parents and coaches as well. When I won U.S. Championships to become the 1986 National Champ, everyone celebrated, even as I was disintegrating in front of their eyes.

On the night I won, I pushed aside the feelings of accelerating depression, anxiety and deep self-loathing. I must be happy, I won? Right? All the adults were so proud. I smiled atop the medal stand, despite the prominent limp I endured to get up there.

These abusive coaching tactics were considered normal and necessary to win. Endorsed or simply ignored by the U.S. Gymnastics Federation (USGF, now USAG), furthered by the national team coaches at training camps, driven into us at home in our own club gyms, and accepted passively by parents.

When I made the team to participate in the World Championships in 1985, we were sent to Montreal (the site of the competition) two weeks ahead of time to train in the facility in which we would be competing. One athlete — the veteran on the team — was scolded about her weight. She was my roommate at the training camp. She gobbled boxes of laxatives in order to achieve the ten pound loss she was told was required to compete. The impact of such bulimic behavior was such that she missed practice for a few days. But she hit the designated number on the scale. This highly decorated and accomplished gymnast remained poised throughout the competition, leading Team USA to a top 6 placement. I suffered a devastating injury — a broken femur — on my last event of the competition. And still, no one questioned the cruel coaching practices.

No parent challenged these draconian tactics practiced by club coaches, national team coaches and judges. My family had several athletes living with us. The girls had moved away from their homes, to live in Allentown, Pennsylvania in order to train at a nationally recognized club — The Parkettes. My team. My mother was called by one of the head coaches if one of her boarders “gained too much weight.” My mom didn’t scream in protest. She felt bad she’d somehow contributed to the “bulking up” of one of the minors in her care. She accepted the scolding as in the bounds of acceptability. She didn’t deny us food but she didn’t have to. We denied ourselves.

I subsisted on a ~400 calorie a day diet. That’s it. I counted every calorie, wrote it down in a little journal, and it included things like “Diet Coke — 0; Gum — 5 cals.” That’s how crazy I was. That’s how much I wanted to avoid a phone call to my mom from one of my coaches.

But this crazy was normal. Eating disorders were encouraged by my coaches. They created my body dysmorphia by saying “You’re a pig.” A look in the mirror would have confirmed that that was not the case. But I believed it because they said it. And no sane person contradicted it. And every other athlete thought and behaved the same way that I did. We adopted utterly unhealthy behaviors as normal, because adults — esteemed coaches and even healthcare professionals — endorsed them, believing they were necessary for us to become champions.

It wasn’t just the coaches that confirmed this delusional thinking. It was medical professionals as well. At a US National Team training camp in 1987, I was sent to a session with the team psychologist. Here’s how that conversation went:

Are your parents overweight?

No.

Do you have siblings?

Yes. One. A brother.

Is he overweight?

No.

So why do you think you struggle?

This was the team psychologist appointed to help us with our performance challenges. She was supposed to be dedicated to helping remove mental blocks — say, if we were having trouble achieving in competitions what we had mastered in practice. If we were prone to “choking.” Instead, the team psychologist hired by USGF chose to further the deranged idea that I was overweight.

If a 99 pound 18-year-old who doesn’t menstruate can believe that she is fat and no one argues, and in fact, all the adults in her life confirm and further the delusion, what insane confused thinking isn’t possible?

Beyond the demented practices around weight, an orthopedist came to our gym every few weeks and shot us up with corticosteroids to ease the pain of our injuries. I trained on what would only later (after I had finished my career as a gymnast) be diagnosed as a broken ankle. I was regularly injected with this steroid so that I could continue training on the swollen, deformed appendage. There was no parental approval, as far as I can remember. This was a doctor, who looked at my purple and grotesquely swollen ankle and basically said: Nothing to see here! Let’s shoot you up and get you on your way!

When parents and adults responsible for the care of children start putting their own egos ahead of integrity and truth and the defense of children — what aren’t they willing to accept? What unhinged falsehood might an otherwise sane adult be convinced of, in order to garner social acceptance and praise from those with perceived power?

You may think you wouldn’t put your child’s health and safety at risk by furthering what may seem a harmless distortion of truth, even endorsed by medical professionals caught up in the same insane whirlwind normalizing abuse of children, but might you?

I think it’s a question parents need to ask themselves each and every day, as the world sends increasingly distorted messages to us regarding what’s in the best interest of our children.

Please keep writing on this.

As the coach of a very large state-level successful high school girls cross country team in an affluent community for nearly a decade, I found the prevalence of eating disorders to be like dandelions. They sprang up everywhere, and they multiplied hyper-exponentially. Having once been anorexic myself, I went in with eyes open, well-equipped (I thought) and on mission to help, and still, I got schooled.

Where was the source? Peer pressure? Yes. Social media? Yes. Parental performance pressure (often cruelly vicarious)? Yes. Aspirations to college scholarships? Yes. Latchkey kids looking for meaning & belonging & attention? Yes. Social contagion? Yes. Avoidance of puberty and all its hassles? Yes. An alternative to suicide? Yes, although sadly, some took a more direct route.

It was like trying to hold back the sea.

Ultimately, these young women (and men too--runners, wrestlers, etc.) try to establish their identity (and affirmation) in and by their performance, atoning, impressing, achieving. This is the way of the world: endless mountains to climb--athletics, career, whatever. And then you die.

Christ Jesus says something different. He already did the ultimate performance, on the cross. He already solved mankind's greatest problem, the source of all heartache: alienation and separation from God.

“Come to Me," He says. "all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light.” (Matthew 11:28-30)

All of this. I counted calories. Starved myself. Wrapped myself in plastic wrap and ran or rode the bike to drop weight. As a gymnast, I controlled my weight by over-exercising and under eating. When gymnastics ended, I became bulimic. I told a counselor about my life as a gymnast and she was shocked and stunned by the fact that no one intervened or thought it was crazy. Hell, at the time, I thought it was normal (as you said). To this day, I have body issues. I am 53 years old and still get disgusted when I look in the mirror. And I am not overweight by any stretch of the imagination. Thank you for sharing, Jen. Thank you.